Against the backdrop of growing wealth inequality and hunger, a rising wave of philanthropy funding is gathering momentum around the world and in India. According to the Global Philanthropy Report 2021, the education sector is specially favoured by philanthropic foundations and high networth individuals, writes Dilip Thakore

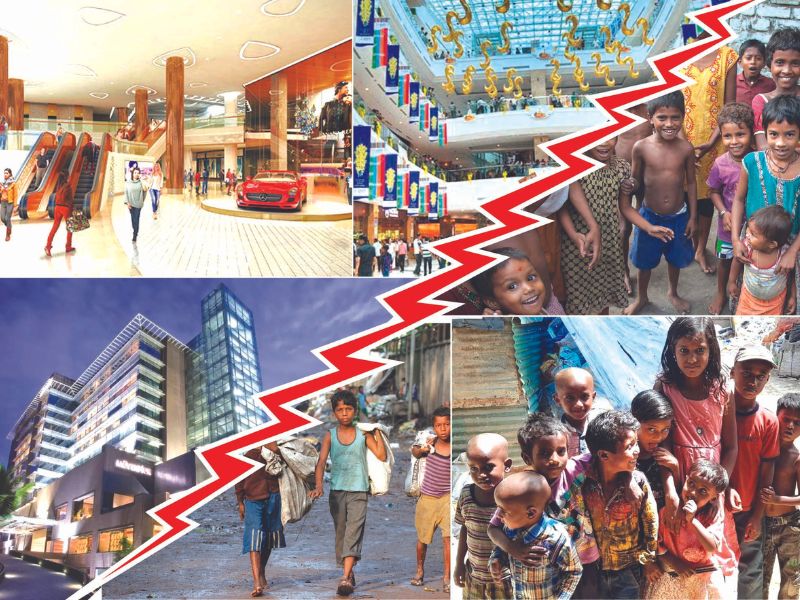

Contrasting images of 21st century India: favourable philanthropy ground conditions

TWO MOMENTOUS RECENTLY released reports on the eve of the 23rd anniversary of EducationWorld — The Human Development Magazine (regst.1999), have the potential to greatly influence the future of India’s children who despite loud official protestations to the contrary, are floundering in shallows and misery.

On October 11, Oxfam International released the fourth edition of its Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index (CRII) 2022. The index reviews the “spending, tax and labour policies and actions” of 161 countries worldwide, including India, during the period 2020-22. “Covid-19 has increased inequality worldwide, as the poorest people were hit hardest by both the disease and its profound economic impacts. Yet CRII 2022 shows clearly that most of the world’s governments failed to mitigate this dangerous rise in inequality. Despite the biggest global health emergency in a century, half of low and lower-middle-income countries saw the share of health spending fall during the pandemic, half the countries tracked by the CRI Index cut the share of social protection spending, 70 percent cut the share of education spending, while two-thirds of countries failed to increase their minimum wage in line with gross domestic product (GDP). Ninety-five percent of countries failed to increase taxation of the richest people and corporations. At the same time, a small group of governments from across the world bucked this trend, taking clear actions to combat inequality, putting the rest of the world to shame.” As a special India report included in this survey elaborates, the government of India — a perennial laggard in social welfare spending, especially on education and healthcare — isn’t in the latter category.

Although Oxfam International is well-known for its left of centre ideological moorings, its experience of conducting wealth inequalities, poverty measurement and hunger surveys for over eight decades commands respect, even if the anti-diluvian solutions anchored in obsolete communist/ socialist ideology, are suspect. Founded by Oxford University academics way back in 1942, Oxfam has established a global reputation for fundraising to provide financial and rehabilitation aid to people and communities devastated by calamities such as floods, earthquakes, famine, war etc. Currently, its international secretariat is based in Nairobi (Kenya) with offices in Addis Ababa, Washington D.C, New York, Geneva, and Brussels. Moreover, it has eponymous affiliates in 21 countries including India (estb.2008), an annual budget of $ 1 billion and 196 employees worldwide on its pay roll. In short, its survey reports and data — even if not its solutions — need to be accorded great respect.

Perhaps coincidentally but simultaneously, two other respectable NGOs — the Dublin (Ireland)-based Concern Worldwide (estb.1968) and the Bonn (Germany)-based Welthungerhilf (1962) — published the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2022, in which India is included among 35 countries suffering ‘serious’ mass hunger. “The hunger levels in both South Asia (where hunger is greatest) and sub- Saharan Africa (where hunger is second greatest) are considered serious. South Asia has the highest child stunting rate and by far, the highest child wasting rate of any world region. Africa South of the Sahara has the highest prevalence of undernourishment and rate of child mortality of any world region. East Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia are experiencing one of the most severe droughts of the past 40 years, threatening the lives of millions. According to forecasts, the climate crisis will be a key factor preventing the world from achieving the second UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 2), ‘Zero Hunger’ by 2030,” warn the authors of GHI 2022.

Although ex facie these two deeply researched and authoritative reports — dismissed by government spokespersons (economics pundit Swaminathan Aiyar, consulting editor of the Economic Times rubbishes GHI 2022 as “statistical garbage”) as extensive tomes written with the sole purpose of maligning India — represent cause and effect, they contain the seeds of a solution. Oxfam’s CRII report provides ample evidence that there’s a large pool of rich citizens in poor India and their number is fast rising.

According to CRII 2022, whereas there were nine US dollar billionaires in India in the millennium year (2000), their number increased to 101 in 2017, and currently there are US dollar 119 billionaires countrywide. Moreover, the authors of the index estimate that the number of rupee millionaires in India rose by 70 per day during the period 2018-22, despite Covid-19 severely disrupting business and the economy. Quite clearly, ground conditions for practice of serious philanthropy to end child hunger and nurture the country’s next generation are promising.

National focus on nurturing generation next is important because the brunt of hunger and malnutrition in 21st century India, is borne by children. According to GHI 2022, 16.3 percent of India’s population is under-nourished with children worst hit. The authors of GHI are forthright and unequivocal: “India ranks 107th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2022 GHI scores. With a score of 29.1, India has a level of hunger that is serious,” they write.

Moreover it’s pertinent to note that the ‘trend values’ of GHI 2022, i.e, metrics to measure hunger are heavily focused on children. The report estimates the proportion of under-nourished population (India: 16.3 percent); child stunting (share of children under age five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic under-nutrition): 35.5 percent; child wasting (share of children who have low weight for their height): 19.3 percent and child mortality (share of children who die before their fifth birthday, partly reflecting the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments): 3.3 percent.

[userpro_private restrict_to_roles=

HIS GLOBAL SURVEY, which ranks glorious shining India— recently proclaimed the world’s fifth largest economy measured by GDP — below Pakistan (#99), Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81) and Bangladesh (84), is — or should be — shocking and disturbing and should prompt deep introspection within right-thinking members of Indian society.

Quite obviously, the problem is not food production per se because the warehouses of the public sector Food Corporation of India are overflowing with rice and wheat staples being consumed by rodents. Moreover, it’s well-established that 40 percent of the country’s horticulture produce (fruit and vegetables) rots in farmyards across the country before it gets to market inflicting an annual loss of Rs.50,000 crore on the Republic’s struggling rural majority. Therefore, India’s pathetic GHI 2022 ranking is not the outcome of failure of the country’s farmers, but of infrastructure deficiency, logistics mismanagement and sustained blocking of a downstream food processing industry of sufficient scale for an economy in which 60 percent of the population is engaged in agriculture/horticulture.

The silver lining of the dark child hunger, stunting and wastage clouds looming over the economy is India’s insufficiently heralded achievement of implementation of a free-of-charge mid-day meal programme in 1.20 million government primary schools countrywide with a fair measure of success. Therefore, ensuring that the majority of India’s 164 million children under age 5, and 111 million below age 14 from bottom-of-pyramid households enrolled in government elementary (classes I-VIII) schools attend daily classes, is of critical importance to eliminate child hunger and malnutrition. However it’s necessary to acknowledge that millions of children are dropping out of public/government schools because the overwhelming majority of India’s 1.2 million government schools are grim, uninviting institutions defined by dilapidated, often dangerous buildings, lack of useable toilets, chronic teacher absenteeism, multi-grade classrooms and rock-bottom learning outcomes.

Therefore, upgradation and improved administration of government schools should be the top priority of state and local governments in particular, because children from poor households who attend them are assured of a nutritious mid-day meal. Yet unless government schools are well-equipped, inviting institutions providing meaningful learning outcomes, they won’t retain children.

One of the most egregious failures of all Central and state governments of post-independence India — and the intelligentsia — has been continuous failure to increase annual expenditure for public education to 6 percent of GDP, a goal set way back in 1967. This glaring government and societal failure is the root cause of the endemic poverty, illiteracy, disease and thousand unnatural shocks that India’s citizens, and children in particular, suffer daily.

With the Central and state governments unable to reduce runaway establishment expenditure, prune non-merit subsidies, slash defence spending, running up huge fiscal and budgetary deficits year after year, they have conspicuously failed to sufficiently nurture and adequately educate India’s children and youth whose number aggregates almost 500 million.

Therefore, this responsibility has devolved upon wealthy citizens, NGOs and right-thinking members of society. Oxfam’s CRII 2022 report details that there’s a large and growing class of billionaires, millionaires and wealthy citizens who despite the worst efforts of the neta-babu brotherhood and leftist intelligentsia, have built substantial fortunes. They should be encouraged and provided stimulating ground conditions to practice serious philanthropy.

In this connection, it’s pertinent to recall that ancient India’s inclusive gurukuls, in which children of rich and poor learned together, were funded as much by merchants and businessmen as by rajahs and princes. This tradition was maintained by successful native business and industry leaders — who Left intellectuals dominating the academy conveniently forget — funded the freedom movement despite every discouragement by the British Raj.

THE INDIAN INSTITUTE of Science, Bangalore (estb.1904), Birla Institute of Technology & Science (BITS), Pilani (1964) and a spate of latter day universities including Amity, Ashoka, Jindal Global, Munjal, Shiv Nadar and Krea among others are testimony to the inherited philanthropic culture of Indian business and industry. Nor is this giving culture of India Inc restricted to higher education. A large number of primary-secondary schools countrywide have also been established by business tycoons and philanthropists.

In the recent (September-October) EducationWorld India School Rankings 2022-23 — the largest schools rankings survey worldwide — league tables, a large number of schools promoted by business and industry houses including Ambani, Birla, Jaipuria figure prominently.

Nevertheless, as detailed in Oxfam’s CRII 2022, given India’s massive 1.4 billion population and geographical spread, the scale of Indian philanthropy is glaringly inadequate. Comments the Global Philanthropy Report: Perspectives on Global Foundations (GPR) 2021, published by the Kennedy School of Public Policy of Harvard University (USA): “Global philanthropy holds immense promise in the 21st century. Global giving is growing, gaining visibility, and creating much-needed change around the world. Over time and across geographies, the world has witnessed a near-universal charitable instinct to help others. Recent years, however, have seen a marked and promising change in charitable giving — wealthy individuals, families, and corporations are looking to give more, to give more strategically, and to increase the impact of their social investments.”

Privately promoted universities: inherited philanthropic culture testimony

GPR 2021 reports that there are 156,894 identified philanthropic foundations in 23 countries worldwide who have donated “irrevocable endowments that are committed in perpetuity to charitable pursuits” aggregating $1.5 trillion (Rs.124 lakh crore). Eighty-five percent of these foundations are sited in the US and Europe with American foundations heading the owned-assets list with $890 billion followed by Netherlands ($108 billion), Germany (92.9 billion), Italy (86.9 billion) and the UK (84.2 billion).

Inevitably, the aggregate asset value of philanthropic foundations in India is relatively minuscule ($0.83 billion or Rs.6,869 crore). Surprisingly, the assets of philanthropic foundations in China aggregate $14.2 billion (Rs.1.1 lakh crore) — way greater than in India. Clearly with a fast-rising number of Indians entering the millionaires, if not billionaires, club every day, there is considerable scope for multiplying the number of foundations and accelerating philanthropy and charitable giving to promote education and eliminate child malnutrition.

The auguries for substantial inflow of philanthropy funding into Indian education are good. According to GPR 2021, the education sector is specially favoured by philanthropic foundations with 35 percent of total funding worldwide flowing into education. In North America (US and Canada), 93.6 percent of philanthropic funding accrues to education institutions and causes, and 47 percent in Asia. “Education is seen as the key to individual opportunity and the engine of national prosperity,” write the authors of the data-rich GPR 2021.

However, the mere existence of a small even if growing minority of HNI (high networth) and wealthy individuals in any society doesn’t per se guarantee philanthropy and fund flows into education institutions. Charitably inclined HNIs are inevitably confronted with the dilemma of having to choose between an array of charities and causes.

American universities attract huge donations, bequests and largesse and have built massive endowment corpuses because they employ professional fundraisers with sophisticated marketing skills to persuade wealthy individuals and families to accord top priority to investing in education institutions for societal and national development.

UNFORTUNATELY because of socialist ideology and mindset which has deeply permeated the academy, intelligentsia and society in the past seven decades since independence, there’s a bad odour about private enterprise and wealth creation, and conversely over-dependence upon the State to subsidise higher education at the expense of primary and secondary education. Therefore, India’s inadequate number of higher education institutions — 41,000 junior and undergrad colleges and 1,057 universities — can accommodate only 35 percent of youth in the 18-24 age group against 60.8 percent in the US, 43 percent in China and 85 percent in South Korea.

“The State, i.e, Central and state governments with their high budgetary fiscal deficits cannot expand education sufficiently. Therefore, private philanthropy is the only hope for increasing India’s low GER (gross enrolment ratio) in higher education and establishing globally benchmarked universities. To encourage philanthropy in education, the Central government needs to provide American style tax incentives to wealthy individuals and corporations to fund higher education institutions. A high powered committee (2012) chaired by N.R. Narayana Murthy, founder-chairman of Infosys Technologies, had recommended 300 percent income tax rebate to individuals and corporates establishing private universities and facilities such as labs, libraries and research centres. The recommendations of this committee should be accepted by government to establish excellent universities to produce a large pool of well-educated, high productivity taxpaying citizens,” says Dr. C. Raj Kumar, founding vice chancellor of the privately promoted O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU, estb.2009), ranked India’s #1 private varsity in the EducationWorld India Higher Education Rankings 2022-23.

A highly-qualified alum of Delhi, Oxford and Harvard universities (to which he won scholarships from philanthropic Western foundations), Raj Kumar is well-versed in the grammar and economics of philanthropy. In the early years of the new millennium, he persuaded steel industry tycoon Naveen Jindal to donate a massive Rs.500 crore to establish JGU on a 40-acre campus in Sonipat in Delhi NCR. Since then after completing construction and operationalisation of the greenfield JGU in record time, he has quickly established JGU’s reputation as India’s most international university also ranked India’s #1 private varsity by Quacquarelli Symonds (QS), the highly reputed London-based global universities ranking agency.

Implicit in Dr. Raj Kumar’s contention that private philanthropy on scale is the “only hope” of establishing globally comparable higher education institutions in India, is advice that ground conditions — by way of government tax incentives and educators’ project management and execution skills — have to be created for philanthropists to invest their savings into nation-building education institutions. Although risk-averse Left academics drawing comfortable Seventh Pay Commission salaries with minimal accountability, tend to believe that tax-paying HNIs and industry tycoons are obliged to donate to charitable and especially education causes, it’s absurd to expect HNIs to recklessly invest hard-earned savings and/or patrimony without due diligence and circumspection.

According to Ashish Dhawan, a Harvard Business School alum, master fundraiser and prime mover behind the blue-chip Ashoka University (estb.2014) promoted with a project cost of Rs.1,500 crore and ranked India’s #2 private university in the EducationWorld India Higher Education Rankings 2022-23, fundraisers have to inspire confidence that they have good money management skills and institutional governance capability.

“Fundraising is serious business, requiring professionalism and attention to detail. Fundraisers should maintain excellent databases of alumni, local industrialists and HNIs committed to supporting education causes; they must present detailed project implementation plans with realistic timelines and build credibility by displaying prudent money management skills from the time they receive their first tranche of investment. They must demonstrate credibility and accountability from the word go,” advises Dhawan, the country’s pioneer venture capitalist (Chrys Capital, estb.1999) who exited business and industry in 2012 to establish the Delhi-based Central Square Foundation with an initial endowment of Rs.50 crore to build capacity and capability in Indian education (see box).

This is good advice because the great majority of promoters, principals and managements of India’s perennially cash-strapped schools and higher education institutions (HEIs) tend to be innocent about the basics of fundraising. They would be well-advised to learn from American universities which have developed fundraising into a well-developed science and art.

For instance, through continuous year-round professionally managed fundraising America’s routinely top-ranked Harvard University has accumulated a stupendous endowment corpus aggregating $53 billion (Rs.4.3 lakh crore) which is carefully invested in stocks and securities to earn the university an estimated $5 billion per year, a sum expended to attract and award scholarships to high calibre scholars (including Dr. C. Raj Kumar quoted above) from around the world. Because of its financial independence and massive endowment, Harvard can afford to follow a means-tested ‘need blind’ admissions policy under which all scholars meriting admission are awarded means-tested scholarships. In addition, Harvard can afford to recruit the world’s best academics and researchers and suo motu undertake massive research projects. New schools, faculties, libraries, sports stadiums etc are funded by award of naming rights to philanthropists, corporates and HNIs.

Nor is Harvard University an exception. Several American, European and East Asian universities have become financially independent academic powerhouses by accumulating endowment corpuses that are mind-boggling by Indian standards.

THE DEGREE TO WHICH fundraising has been professionalised “into a science and near art form” by America’s best universities is testified by Bharati Thakore, a media and communications alumna of Denison University, USA (DU, estb.1831) and promoter-CEO of the Mumbai-based New Millennium Education Partners Pvt. Ltd (estb.2017), a consultancy whose transnational clients list includes the Beau Soleil School (Switzerland), H. Farm International (Italy), and Corvuss American Academy, Karjat (Maharashtra) among several other domestic schools and NGOs.

According to Thakore, Denison University’s Alumni Affairs division sited within the varsity’s sprawling campus is to all intents and purposes run like an autonomous corporation with 46 full-time highly qualified business professionals led by a vice president for institutional advancement.

“This team engaged in fundraising full-time is supplemented with 1,033 volunteer members who also raise funding for DU. As an alumna, I was one among 7,864 donors who received five well-crafted letters this year to contribute any amount over $100 towards the university’s endowment corpus. This extraordinarily personalised and professional fundraising has enabled DU to raise $7.89 million (Rs.65 crore) thus far this year. Moreover, DU has accumulated an endowment corpus of $1 billion, which is large for a small university of 2,500 students. Sustained, highly professionalised fundraising has enabled DU to follow a need blind admissions policy and provide ultra-modern fully digitalised academic, co-curricular and sports education infrastructure and excellent residential accommodation to students on its superbly landscaped 850 acres campus,” says Thakore.

World’s wealthiest universities

(endowment corpuses in $)

Harvard University (USA) 53.20

Yale University (USA) 42.30

Stanford University (USA) 37.80

Princeton University (USA) 37.00

Massachusetts Institute of

Technology (USA) 27.40

University of Pennsylvania

(USA) 20.50

University of Notre Dame

(USA) 18.40

Texas A&M University (USA) 16.90

University of Michigan —

Ann Arbor (USA) 16.80

Washington University in

St. Louis (USA) 13.70

Cambridge University (UK) 8.18

Oxford University (UK) 7.00

IIT-Bombay 0.11

IIT-Madras 0.08

IIT-Delhi 0.04

IIT-Kanpur 0.03

While a few new genre top-ranked universities such as Ashoka, Jindal, Krea and most recently Plaksha (Mohali) have learned and adapted the fine art of fundraising from American academia, the great majority of public (government) universities — some of whom are over 150 years vintage — are hopeless novices in this art and abjectly dependent upon grudging government largesse.

This is reflected in their shabby, rundown campuses with low-grade residential accommodation and minimal research output. However there are exceptions. It’s well-known that India’s six vintage Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) have accumulated large — by Indian standards — endowment corpuses.

For instance, IIT-Bombay (estb.1960) owns a sizeable endowment corpus of Rs.966 crore. This is the outcome of the institute’s management having established a highly professionalised ARC (alumni and corporate relations) office on its 300- acre campus in suburban Mumbai. This office is reportedly manned by 35 full-time employees engaged in continuous fundraising. It maintains an up-to-date database of its 65,000 alumni most of whom have risen to high positions in the corporate world and are grateful to the institute for having provided them excellent technical and engineering education at over-subsidised rock-bottom price.

However, despite being a publicly funded institution, the management of IIT-B proved to be surprisingly reluctant to share its fundraising expertise for the benefit of Indian education. Despite your correspondent complying with all pre-conditions (written questions, vetted copy matter etc), Dr. Ravindra Gudi, dean of ARC, responded with exaggerated caution to an innocuous request for information and opinion and finally failed to respond to two written questions related to IIT-B’s relatively successful fundraising record.

Sangita Chima

THIS EXCESSIVE CAUTION in sharing information for the benefit of the country’s educators community and public, is not entirely unwarranted. The all-powerful and omniscient neta-babu brotherhood which controls the purse-strings of heavily-subsidised higher education institutions, especially the IITs, doesn’t appreciate financial autonomy and reduced dependency on the education ministry. Way back in 2004 when Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi was Union HRD (education) minister in the Vajpayee-led BJP government, he issued an order to reduce annual tuition fees of IIMs to Rs.30,000 (from Rs.1.75 lakh) and introduced a programme under which all alumni and other donations to the IITs would have to be routed through a Bharat Shiksha Khoj trust controlled by the education ministry.

St. John’s High’s Kavita Das

Similarly, when Smriti Irani was appointed the first HRD minister of the Modi-led BJP which swept to power at the Centre in 2014, she made a determined effort to pack the governing boards of the IIMs with party acolytes to acquire control of their endowment corpuses. It took a massive media uproar led by EducationWorld to reverse this coup and Irani’s ouster from the HRD/education ministry in 2016.

Nevertheless, there’s no denying that since then, primarily because of pressure from state governments which have licensed the promotion of a spate of private universities — education is a concurrent subject under the Constitution — the attitude of BJP governments at the Centre and in 17 states in which it is the ruling party, has mellowed. Consequently, the fundraising for institutional growth and development has also spread to the K-12 education sector. Several progressive school managements have successfully tapped their alumni and parents and local communities to pay for the education of children from neighbouring EWS (economically weaker sections) admitted in the interests of ensuring diversity on school campuses.

Among primary-secondaries that have learned the art of fundraising is St. John’s High School, Chandigarh (SJHS, estb.1969) ranked the country’s #1 boys day school in EWISR 2022-23. “Although as a minority-promoted school, we are exempted from s. 12 (1) (c) of the RTE Act which requires all schools to allocate 25 percent of seats in classes I-VIII, we voluntarily admit a large number of children from EWS households every year. Currently, we have 300 children of our total enrolment of 2,000 who are provided free-of-charge education. We have been quite successful in raising funding from our alumni and have built a sizeable corpus managed by the governing board through which we are able to award generous scholarships to EWS children. Our alumni association maintains an excellent, up-to-date database of members and whenever we require project finance, we inform the association which always responds positively. For instance in 2018, they funded constructed a fully-equipped VET (vocational education training) centre maintained at a cost of Rs.22 lakh per year. Moreover in 2021-22, the school’s alumni gifted the school a fully-equipped pistol and rifle shooting range. I believe excellent relationship with our alumni and parents communities is the outcome of the values of compassion, sharing and inclusivity that we have integrated into the school’s curriculum,” says Kavita Das, an alumna of Delhi University and principal of St. John’s High since 2007.

Fundraising success stories in primary-secondary schools on the lines of the SJHS experience, are not a rarity. It’s well-known that the top-ranked vintage legacy schools including Woodstock, Mussoorie, Daly College, Indore, The Doon School, Dehradun have accumulated impressive endowment corpuses estimated at Rs.80-100 crore on which they draw to provide scholarships, expand and regularly renovate on-campus academic, co-curricular and sports infrastructure.

However despite repeated emails and telephone calls, principals of the said schools declined to share their fundraising strategies and experience with EducationWorld and the educators’ community. Such self-centredness presumably born out of unwarranted insecurity, is deplorable and not in the national interest.

BUT ALTHOUGH unwarranted secrecy and reluctance to share best practices is pervasive in Indian education, there are exceptions. Sangita Chima, an alumna of Andhra and Annamalai universities and currently principal of the superbly furbished Amity International School, Dubai, chalked up a good fundraising record at the vintage Lawrence School, Lovedale (LSL, estb. 1858) where she served a five-year term as principal (2012-17).

“During my term as principal at LSL, we steadily built up the school’s endowment corpus which is currently estimated at Rs.10 crore. However, the management draws upon it only for emergency pay-outs. Funding for specific projects including curriculum enrichment and professional development programmes is raised by way of alumni contributions. LSL maintains meticulous batch-wise alumni records. Every year, a new projects and initiatives wish-list is circulated to all alumni batches and invariably one or more batches collect funding for specific projects and send it to the school for project execution. When I was principal at LSL, we raised Rs.10 crore to completely upgrade our cricket pavilion and football grounds,” recalls Chima.

An alumna of Jadavpur University, Kolkata and IIM-Calcutta and pioneer in the holiday homes time share industry in India as CEO of Resort Condominiums India in the 1980s, Shukla Bose, founder trustee of the Bengaluru-based Parikrma Humanity Foundation (PHF, regstd. 2003), is another highly skilled fundraiser.

Since the foundation established its first free-of-charge primary school for slum children in Bengaluru two decades ago, the number of Parikrma K-10 English-medium schools affiliated with the Karnataka state examinations board has grown to four with an aggregate enrolment of 2,000 children mentored by 238 teachers. Moreover PHF has also established a junior (higher secondary) college and teacher training centre which has upskilled 2,300 government school teachers. The foundation raises a substantial sum of Rs.14 crore per year to fund its operational expenses from over 65 committed corporate and other donors, but hasn’t yet built an endowment corpus.

“Although we are fortunate to have a large number of corporate donors who fund us under the CSR (corporate social responsibility) mandate of the Central government, as also a substantial number of generous foundations and individual patrons, our annual revenue just about covers operational expenses. Administrative expenditure has risen steadily to almost 10 percent of receipts because corporate donors require considerable documentation and compliance with several Central and state government laws. Unfortunately, despite our good track record of thoroughly educating our children and placing them in blue-chip companies, we haven’t succeeded in building an endowment corpus. This requires large-scale American style philanthropy. Regrettably, most people in India don’t make the distinction between philanthropy and charity. Philanthropists invest in socio-economic development, whereas charitably inclined people invest for personal salvation in feel-good causes. School teachers and leaders should teach children to become philanthropy-minded from early years and advise them that if they can’t give money, they should give their time for community development projects,” says Bose.

The silver lining of the widening gap between rich and poor in post-liberalisation Indian society — inevitable for a country that belatedly took the capitalist road in the new millennium — is that a rising wave of philanthropic impulse is sweeping across the country. The sustained propaganda of self-serving Left intelligentsia and commentariat that rich elites are congenitally incapable of aiding and enabling the poor to transform India into a middle class nation, has been disproved by the experience of Western

democracies. Although seemingly forgotten, Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy of the trusteeship model under which the wealthy minority should hold their wealth in trust for the benefit of the poor, has permeated the collective sub-conscious of Indian society. This is evidenced by the large and growing number of private schools and universities supported and funded by alumni and corporates which have matured into top-ranked institutions.

However for private philanthropy in education to take off in a big way, institutional managements and leaders have to learn to inspire a larger number of wealthy citizens to fund them by building donor confidence through credible accountability systems and processes. The good news is that awareness of the importance of professionally managed fundraising and accountability to donors is beginning to permeate the corridors of the Central and state governments.

On August 17, the Union education ministry issued a formal directive to all Central government-funded universities to initiate fundraising programmes “for the purpose of mobilizing donations, funds and contributions from well-wishers, alumni, philanthropists and industries (sic) for the development of students faculties and institutions”. In the circular, the ministry has directed that all 85 Central universities countrywide constitute seven-member CUEF (Central University Endowment Fund) committees comprising the vice chancellor, a finance officer, two professors from separate departments and three donors nominated by the executive council to govern their endowment corpuses. Significantly, the notification adds that “a reasonable percentage of the fund, not exceeding 50 percent, may be spent annually with a view to maintain a good corpus for the future”.

Whether this initiative which foretells heavy bureaucratisation and documentation, will enable Central universities to reduce their dependency on government funding is a moot point. However, it’s importance is that it has granted official approval and conferred the halo of respectability on institutional fundraising and financial independence.

Clearly, powerful new winds of change are blowing through the country’s moribund education sector. The wide gap separating Indian industry from the academy may well be bridged by private philanthropy. Providentially, there is rising awareness within all the great estates of the republic — parliament, government, the judiciary, media, India Inc and the rapidly expanding middle class — that education, aka human capital development, is the necessary pre-condition of wealth generation and national development.

[/userpro_private]

Add comment